Daylight Saving Time: A Global Perspective on Time Changes

- Cougan Collins

- Mar 8, 2025

- 9 min read

Historical Context

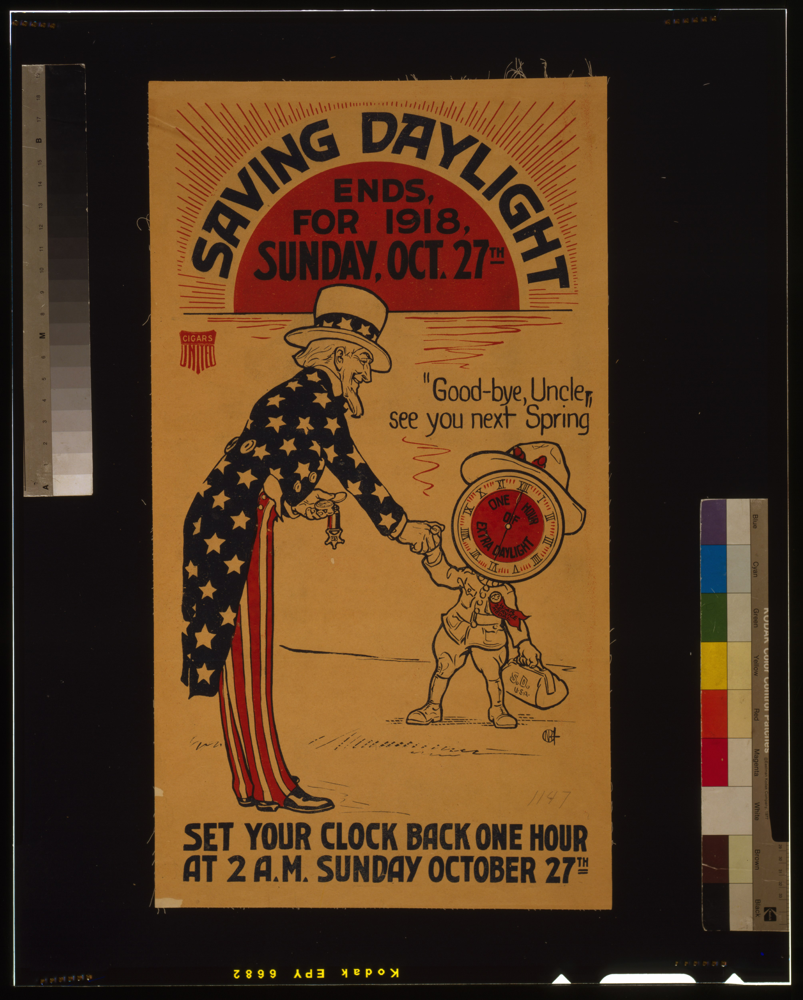

Figure: A 1918 U.S. poster marking the end of daylight saving time after World War I. It features Uncle Sam shaking hands with a clock-headed figure representing “one hour of extra daylight” (Saving daylight ends, for 1918, Sunday, Oct. 27th Set your clock back one hour at 2 A.M. Sunday October 27th. | Library of Congress). The modern idea of daylight saving time (DST) traces back to proposals in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In 1784, Benjamin Franklin jokingly suggested people wake earlier to save candle wax, but he did not propose changing clocks (Daylight saving time - Wikipedia). The first serious clock-change idea came from New Zealand entomologist George Hudson in 1895, and Britain’s William Willett campaigned for “summer time” in 1907 (Daylight saving time - Wikipedia). DST was first enacted during World War I: Germany and Austria-Hungary advanced their clocks on April 30, 1916, to conserve coal, and other nations followed (Daylight saving time - Wikipedia). The United States first adopted DST in 1918 as a wartime measure and nicknamed year-round DST “War Time” during World War II (Daylight saving time - Wikipedia). After the wars, DST policies fluctuated. Farmers often opposed DST (morning dew and livestock routines don’t reset with the clock), and indeed, many countries repealed wartime DST shortly after WWI (Daylight saving time - Wikipedia). It wasn’t until 1966 that the U.S. standardized the schedule with the Uniform Time Act. During the 1970s energy crisis, DST was temporarily extended year-round in the U.S., but pre-dawn darkness led to public complaints, and the experiment was dropped within a year (Daylight saving time - Wikipedia). Over the decades, DST has continued to spark debates about its necessity and effectiveness.

International Comparisons

Figure: Daylight saving time around the world. Countries in blue (Northern Hemisphere) and orange (Southern Hemisphere) currently use DST during part of the year, while dark gray areas never use it and light gray areas formerly used DST. Only about one-third of countries worldwide still practice seasonal clock changes, mostly in Europe and North America (Daylight saving time and time zones in countries around the world: Key facts | Pew Research Center). Europe has the highest adoption, virtually all European nations observe DST (except a few like Iceland, Russia, Belarus, and Turkey) (Daylight saving time and time zones in countries around the world: Key facts | Pew Research Center). North America observes DST in most of the United States (aside from Arizona, Hawaii, and U.S. territories) and most of Canada, as well as in Mexico’s northern border region (Daylight saving time and time zones in countries around the world: Key facts | Pew Research Center) (Daylight saving time costs US almost $434 million in productivity: Study - Washington Examiner). In contrast, Asia and Africa largely do not use DST. Equatorial countries see little daylight variance and have mostly abandoned the practice if they ever used it (Daylight saving time - Wikipedia). In fact, Egypt is currently the only African country to observe DST, having reinstated it in 2023 to save energy (Daylight saving time and time zones in countries around the world: Key facts | Pew Research Center) (Daylight saving time and time zones in countries around the world: Key facts | Pew Research Center). Many nations that once used DST have decided to stop. About half of all countries tried DST in the past but ended it, including recent exits in the 2010s by Russia, Turkey, Iran, Namibia, and others (Daylight saving time and time zones in countries around the world: Key facts | Pew Research Center). In 2022, Mexico’s congress voted to abolish DST for most of the country as well (Daylight saving time and time zones in countries around the world: Key facts | Pew Research Center). The patchwork of DST observance can even vary within countries: for example, parts of Australia (like Queensland and Western Australia) opt out of DST while other states participate (Daylight saving time and time zones in countries around the world: Key facts | Pew Research Center). These international differences reflect each region’s latitude, energy policies, and public preferences about balancing daylight in the mornings versus evenings.

Scientific Effects of Time Changes

Seasonal time changes impact human routines in measurable ways. Researchers have examined how the one-hour shift affects sleep patterns, health, and the economy:

Sleep Disruption & Fatigue: Losing an hour by “springing forward” disrupts our circadian rhythm. People get less sleep right after the clock changes and often feel groggier and less alert at work and school (DST's Impact on Car Accidents | Charbonnet Law Firm). This acute sleep loss can decrease productivity and increase the chance of mistakes or accidents.

Heart Health: Studies link DST transitions to cardiovascular risks. One study in Michigan found a 24% spike in heart attacks on the Monday following the spring clock change (Here’s your wake-up call: Daylight saving time may impact your heart health | American Heart Association). Finnish researchers similarly observed an 8% higher rate of ischemic stroke in the first two days after DST begins in spring (Here’s your wake-up call: Daylight saving time may impact your heart health | American Heart Association). Experts believe the sudden shift in sleep and biological clocks stresses the body (Here’s your wake-up call: Daylight saving time may impact your heart health | American Heart Association).

Safety & Accidents: The immediate aftermath of DST change sees more accidents. Fatal car crashes increase by an estimated 6% in the week after clocks move forward (DST's Impact on Car Accidents | Charbonnet Law Firm), likely due to driver fatigue and darker mornings. Workplace injuries have been reported to rise on the Monday after the spring shift, especially in jobs involving heavy machinery, as tired workers are more prone to error (Daylight saving time costs US almost $434 million in productivity: Study - Washington Examiner).

Energy Use: A primary original rationale for DST was to save energy by reducing the need for electric lighting in the evening. However, modern studies suggest the energy benefit is marginal. For instance, the U.S. Department of Transportation once found a roughly 1% electricity savings during DST, but newer research finds little to no net energy saved (Does Daylight Saving Time Really Save Energy? - Entergy Newsroom). In some cases, DST may increase energy consumption because people use air conditioning more on warm, bright evenings (Does Daylight Saving Time Actually Save? Research Shows Costs Outweigh Benefits - UConn Today). The extended daylight also encourages more driving (for shopping or leisure), potentially offsetting any conservation of electricity (Does Daylight Saving Time Actually Save? Research Shows Costs Outweigh Benefits - UConn Today).

Economic Costs: Shifting clocks twice a year may carry hidden economic costs. Studies have estimated hundreds of millions of dollars in lost productivity due to disrupted sleep and schedules. In the United States alone, the annual cost of DST-related disruptions (from sleep-deprived workers, health care costs for heart attacks, accident responses, etc.) has been pegged at $430+ million (Daylight saving time costs US almost $434 million in productivity: Study - Washington Examiner). While retail and recreation industries often welcome the later sunsets of DST (people may shop or dine out more with evening light), these gains are hard to quantify and may be outweighed by the broader productivity dip and health costs of the transition.

Public Opinion and Debates

Public sentiment about daylight saving time is mixed, but one trend is clear: many people dislike switching clocks twice a year. In the U.S., surveys show a majority of Americans want to eliminate the semiannual time change and stick to one fixed time year-round (Dislike for changing the clocks persists - AP-NORC). A 2021 AP-NORC poll found only 25% of Americans favored the status quo of changing clocks; 43% preferred permanent standard time, and 32% wanted permanent DST (Dislike for changing the clocks persists - AP-NORC). This lack of consensus on which time to choose (more morning light versus more evening light) has made it tricky for lawmakers to act. Even so, there have been strong legislative pushes to reform DST. In the U.S., the Sunshine Protection Act, a proposal to make DST permanent nationwide, passed the Senate in 2022 (Does Daylight Saving Time Actually Save? Research Shows Costs Outweigh Benefits - UConn Today). Although that bill stalled in the House, several states have passed their own measures expressing a desire for year-round DST or standard time (changes that require federal approval). Across the Atlantic, the European Union faced a similar debate. In 2018, after an EU-wide survey showed an overwhelming majority of 4.6 million respondents wanted to stop seasonal clock changes, the European Parliament voted to phase out DST by 2021 (European Parliament delays plan to end clock changes – POLITICO). Each member country would decide whether to stay on permanent “summer” or “winter” time (European Parliament delays plan to end clock changes – POLITICO). However, implementation has been slow, as of 2025, the EU clock changes are still happening, pending coordination between countries. Elsewhere, countries like Russia and Argentina have already opted to scrap DST and stick to one time year-round after public and political consensus against the practice (Daylight saving time and time zones in countries around the world: Key facts | Pew Research Center). Overall, the global trend has been toward questioning the merit of DST. Polls and proposals in many nations indicate that people value consistency (no clock changes) even if they disagree on the preferred alignment of sunlight. The debate continues, but public opinion generally leans toward simplifying time by “locking the clock” in one position.

Geographical Impacts and Unique Time Challenges

Figure: The midnight sun at Nordkapp, Norway (71° N latitude). In summer, at high latitudes, the sun remains visible at local midnight (as seen here just before 1 AM), a dramatic example of extreme daylight hours. Different regions of the world face unique timekeeping challenges due to geography:

Polar Day & Night: Near the Arctic and Antarctic Circles, summer brings 24-hour daylight while winter brings weeks of darkness. In places like northern Norway, Alaska, or Antarctica, this midnight sun and its winter counterpart (polar night) mean the human daily cycle can drift from the clock. Even with DST, people up north must cope with long periods of either continuous light or darkness, which can disrupt sleep and require special schedules (for example, blackout curtains in summer or daytime lighting in winter).

Tropical Consistency: By contrast, equatorial regions (Central Africa, Southeast Asia, etc.) get roughly 12 hours of daylight year-round. There is little seasonal variation in sunrise/sunset times, so DST provides no real benefit (Daylight saving time - Wikipedia). That’s why most countries in the tropics don’t bother with clock changes. For instance, nations from Indonesia to Uganda stay at the same time throughout the year, and daylight varies by only an hour or less over seasons.

Time Zone Oddities: The globe is divided into time zones, but not always neatly. China, though geographically spanning five standard time zones, uses a single national time (Beijing Time, UTC+8) for the whole country (Time in China - Wikipedia). This creates a discrepancy in its far-western regions (like Xinjiang), where solar noon can be as late as 3 PM by the clock. Residents often adjust their work hours informally to cope with the off-kilter solar time. In India (UTC+5:30) and Nepal (UTC+5:45), the official time is set in half-hour or even quarter-hour increments (Why Are Some Time Zones 30 Minutes Off Instead of an Hour?). These unusual offsets split the difference between neighboring whole-hour zones to better match local solar time, a unique solution to geographical longitude.

Regional Exceptions: Large countries often have internal differences. In Australia, only the southern states observe DST, while Queensland and Western Australia do not, causing a two-hour time difference between some cities in summer (Daylight saving time and time zones in countries around the world: Key facts | Pew Research Center). Brazil formerly had DST in its southern regions (closer to the subtropics) but not in equatorial northern areas. And within the U.S., Arizona (except Navajo Nation) and Hawaii remain on standard time year-round, so a flight from Los Angeles to Phoenix might have no time difference in winter but a one-hour difference in summer (Daylight saving time costs US almost $434 million in productivity: Study - Washington Examiner). These regional quirks require residents and travelers to be mindful of local rules.

Cultural and Political Factors: Sometimes, practices are tailored to local customs. For example, Morocco effectively stays on DST (UTC+1) all year but pauses it during the holy month of Ramadan (Daylight saving time - Wikipedia). Each spring, Morocco temporarily reverts to standard time (UTC+0) so that the daily fasting schedule aligns better with sunrise and sunset during Ramadan, then returns to DST afterward. This annual adjustment is unique to Morocco’s blend of religious and practical timekeeping. In another case, Samoa in the Pacific moved the international date line in 2011, essentially “skipping” a day, to align its workweek with trading partners in Australia and New Zealand. This wasn’t about DST, but it highlights how politics and economics can prompt significant time zone changes for a region’s benefit.

In summary, daylight saving time remains a fascinating mix of history, science, and local preference. Its original goal was to make better use of daylight, but its actual effects on energy, health, and lifestyle are continually debated. Around the world, some societies embrace the extra evening light, while others have opted out of the ritual of changing clocks. Meanwhile, geography ensures that one size never fits all for timekeeping, from equatorial nations that stay constant to polar communities with extreme daylight swings. The ongoing discussions about DST’s future show that how we set our clocks is about more than time, it’s about what we value in our days, whether it’s safer mornings, brighter evenings, or simply consistency. As we gain and lose that single hour each year, the world watches to see if tradition will hold or if we’ll eventually keep time on one steady track year-round. This article was produced using deep research through ChatGPT.

Comments